COVID-19 is not ebola or the bubonic plague - NZ experts confirm the risk in healthy children of death of COVID-19 is lies somewhere between infinitesimal and minuscule.

**This story was first published in October. It’s being republished today as the government has announced plans to roll-out vaccines to children.

The FDA has authorised Covid vaccination for kids, after a US advisory panel endorsed it, paving the way for New Zealand to do the same. But just because we can, does that mean we should*?**

This week, 18 health advisers in the United States gathered to nut out the case for vaccinating children against Covid-19.

When it came to crunch time, 17 cast their votes in favour. One infectious diseases expert abstained. On Saturday the FDA authorised the use of the Pfizer vaccine for children aged 5-11.

But the decision is more fraught than those numbers suggest, because the risk of healthy 5-11-year-olds getting seriously ill from Covid is small. It's a tricky line call, with a dose of medical ethics thrown in.

As Immunisation Advisory Centre (IMAC) director Nikki Turner puts it, “I don't have an answer for you, because I think there's pros and cons”.

The Pfizer vaccine for children is ⅓ of the adult dose.

The Pfizer vaccine for children is ⅓ of the adult dose.

What is the risk to children from Covid-19?

In all the anxiety around classroom ventilation and children returning to school, a critical fact seems to have been lost – most kids who develop Covid get very mild infection. Many won't even know they've got it.

And the risk of death for a healthy 5-11-year-old lies somewhere between infinitesimal and minuscule .

That's because Covid is a disease hugely influenced by age. As one analysis put it, someone older than 85 is more than 10,000 times more at risk of dying than a child younger than 10. And an unvaccinated 10-year-old has a lower death risk than a vaccinated 25-year-old.

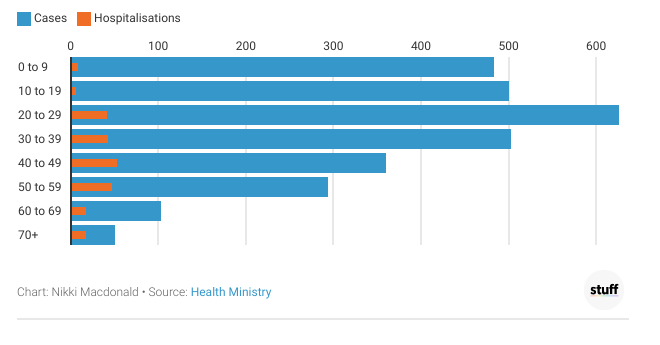

Age breakdown of New Zealand's Delta outbreak

Cases and hospitalisations in New Zealand's Delta outbreak, by age

In New Zealand's Delta outbreak (as of late October), 0-9-year-olds made up 17 per cent of all cases, with 483 kids testing positive. But they represented only 4 per cent of all hospitalisations, with 9 kids landing in hospital. None needed intensive care, or died.

In the latest New South Wales outbreak, from June to October, 455 youngsters aged 0-9 were in hospital with Covid. That's 5 per cent of all cases in that age group, compared with 62 per cent in infected 80-89-year-olds. Six under-10s were admitted to ICU. None died.

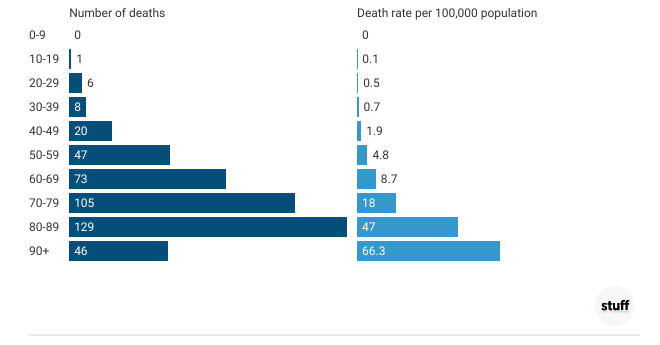

Age of influence

New South Wales Delta outbreak deaths following recent infection with COVID-19, by age group, from 16th June to 9th October 2021

However, research suggests the hospitalisation numbers are likely to be an overestimate, as up to 80 per cent of Covid-positive children in hospital will be there with Covid, not because of Covid. Sydney 15-year-old Osama Suduh, for example, died in hospital with Covid, but from pneumococcal meningitis.

A Californian study found 40 per cent of kids in hospital with Covid had no symptoms, and 45 per cent of admissions were unlikely to be because of Covid.

When it comes to children, Covid-19 is not the bubonic plague, says Otago University professor of women's and children's health Peter McIntyre.

“OK it's bad, but it's not ebola or 1918-19 flu. We've got to be a little bit balanced.’

Paediatric infectious disease specialist Tony Walls says the risk to healthy children from Covid is very low.

Paediatric infectious disease specialist Tony Walls says the risk to healthy children from Covid is very low.

Paediatric infectious disease specialist Tony Walls agrees. “The risk of severe disease in [healthy] children under 12 from Covid-19 is probably lower than from influenza. That does not apply for adults.”

But there are some children at risk of getting really sick – those with other major health problems.

That includes children with suppressed immune systems following organ transplants and children with heart or lung problems. Down Syndrome also puts kids at greater risk from Covid.

It's understood the six children who needed intensive care in New South Wales all had other significant health issues.

Research shows hospitalisation figures for kids are overcounted, as many are in hospital with Covid, rather than because of Covid.

Research shows hospitalisation figures for kids are overcounted, as many are in hospital with Covid, rather than because of Covid.

Kids with severe neurological problems, such as severe cerebral palsy, are also high risk, Walls says.

“Every winter, we get children who die with any number of viruses – influenza, RSV – who come in, they can't cough, they're enormously disabled. They get a chest infection and they fade away and die with it.”

Auckland University child health specialist Jin Russell says an analysis of multiple studies of kids in hospital due to Covid-19 found 1 in 20 children with other health conditions got sick enough to need oxygen or help breathing, compared with 1 in 500 healthy children.

The problem is that Delta's rapacious spread makes it a numbers game. Every unvaccinated child is likely to eventually get the virus, which means even low likelihood tragedies will happen.

“If we have a high level of community transmission, even rare outcomes like hospitalisation of children, can be commonly seen. This is what has happened in the USA, in states where Delta is surging,” Russell says.

There are also still unknowns. It's not clear to what extent children are affected by long Covid – symptoms such as headaches and fatigue that can linger months after even mild infections.

There could also be interactions between Covid and other viruses, such as the seasonal infection RSV, which can be dangerous for young children.

A British panel found the benefits of vaccinating teenagers were marginal, but the jabs were approved on “public health grounds”.

A British panel found the benefits of vaccinating teenagers were marginal, but the jabs were approved on “public health grounds”.

What are the risks and benefits of vaccinating children?

Measles, diphtheria, polio – our childhood vaccination programme is designed to prevent children getting dangerous diseases. Often, they're diseases more hazardous to infants than to adults.

Covid is the reverse. So does the case for vaccination stack up? Walls sums up the conundrum.

“There are almost no vaccines that we give to children, where we give it primarily to protect others in the community. When we vaccinate young children, we're doing it to protect them. The extremely low rate of severe disease in children this age means that it is a difficult ethical issue."

In Britain, the advisory group assessing vaccination for 12-15-year-olds found the individual health benefits of vaccination were small for teens with no other health conditions. While the benefits were "marginally greater" than known harms, the panel found they did not justify a universal vaccination programme for healthy teens.

The health benefits of vaccinating all younger children are likely to be just as small.

Pfizer says its child vaccination regime is safe and effective.

Pfizer says its child vaccination regime is safe and effective.

Pfizer's child trial studied 2268 children aged 5 to 11 who got placebo or two kid-sized shots three weeks apart. The regime was deemed safe and effective, with similar minor side effects as those experienced by teens. But the trial is too small to detect rare side effects.

Walls says the case for vaccination is likely to stack up for those high-risk children, who have other health problems. You might also want to vaccinate children who have family members with weakened immune systems. But for normal, healthy children, the equation is less clear.

“The question of whether they should be vaccinated, for their own personal protection, is a difficult one. And many would say that it wouldn't be necessary.”

Otago University professor of women's and children's health, Peter McIntyre, says there’s a good case for vaccinating high risk children, but the justification for vaccinating all kids is less clear.

Otago University professor of women's and children's health, Peter McIntyre, says there’s a good case for vaccinating high risk children, but the justification for vaccinating all kids is less clear.

McIntyre agrees the decision is not straightforward.

“I think paediatricians would be very keen for that group of vulnerable children, who would be vulnerable no matter what virus they came across, but maybe just that much more vulnerable to Covid, to get protected.

“Then for other children in the 5-11-year-old age group, you really have to put a high premium on ensuring safety. Because we know that once you've excluded that probably 2 or 3 per cent of children with severe other problems, then the rest of the children, the chance of them getting even more than a cold or something they may not even notice, is really very small.”

Some members of the US panel wanted to emphasise that high-risk children with other conditions or weak immune systems should get the vaccine, but healthy children could hold off.

In terms of safety, there are two upsides to the proposed child vaccination regime, McIntyre says. The first is that the dose is one-third of the adult dose, so it's likely to cause fewer side effects.

The second is that the Pfizer vaccine's most significant side effect – heart inflammation problem myocarditis – is much less common in younger children than teenagers.

“So in pre-adolescent children you would predict it might be quite rare. But we're obviously not sure about that.”

In Britain, they did end up vaccinating 12-15-year-olds, with a single Pfizer dose. That's because the country's chief medical officers decided it was warranted on “public health grounds”, considering the effect widespread transmission in schools would have on children's education.

Māori Pandemic Group co-leader Sue Crengle says education and social development risks should be weighed up alongside health risks.

Māori Pandemic Group co-leader Sue Crengle says education and social development risks should be weighed up alongside health risks.

Māori Pandemic Group co-leader, Professor Sue Crengle, believes the wider benefits of vaccination should be taken into account.

“If young people contract Covid at school, and they take it home, there may well be adults in their home that haven't been vaccinated, or that have been vaccinated but get breakthrough infections. And some of those adults may be more vulnerable to more severe Covid.

“Most breakthrough infections generally are milder, but if you've got lung disease, or you're 85 then you're likely to get the more severe breakthrough Covid.

“I think it needs some careful thought around weighing up the health risks, the education and social development risks, and the protection in terms of the wider family and community, versus any potential adverse effects of the vaccination. And that's complex.”

Vaccinating boys against rubella is the only NZ example experts can think of where kids are jabbed for the sole purpose of preventing a disease’s spread in the community.

Vaccinating boys against rubella is the only NZ example experts can think of where kids are jabbed for the sole purpose of preventing a disease’s spread in the community.

Is it ethical to vaccinate children to protect adults?

Remember that rubella or MMR jab you got as a kid? That's the only example experts can think of where we vaccinate children to protect adults.

Rubella is a mild disease that would not justify a jab, were it not for the fact it can cause severe damage to unborn babies. So for boys, getting the jab has no health benefit. It's a purely altruistic act to help prevent the disease spreading in the population.

Otago University bioethicist Janine Winters says there is an argument for vaccinating children to prevent disease spread, as New Zealand's greatest Covid-fighting barrier is capacity in the health system.

However, the most important question is still “Does it benefit the individual child?"

Otago University bioethics lecturer Dr Janine Winters says the most important question for those considering child vaccination is ‘Does it benefit the child?’

Otago University bioethics lecturer Dr Janine Winters says the most important question for those considering child vaccination is ‘Does it benefit the child?’

As a former child palliative care specialist, Winters thinks about the ethics of child treatment decisions.

“I have a special interest in decision-making with children. How do you weigh benefit and burden? You have to do that for the child.”

“We can't sacrifice the children for the sake of the old people. That's not OK. Fortunately, I don't think we're making that choice with this vaccine.”

Covid in children is like chicken pox – a mostly mild disease, Winters says. However, she did vaccinate her own kids against chicken pox. That's because being sick isn't fun; serious complications are rare, but possible; and infection comes with longer-term risks, including later susceptibility to shingles.

Many children will experience a cold-like illness if infected with Covid-19, but children with underlying health conditions or who are Māori and Pasifika are at greater risk of severe illness.

Many children will experience a cold-like illness if infected with Covid-19, but children with underlying health conditions or who are Māori and Pasifika are at greater risk of severe illness.

But even if the vaccine is as safe as expected in children, the “infinitesimal” risk of healthy kids getting critically ill from Covid means vaccinating children should not be a high priority, Winters says. And parents should have more discretion.

“I think the government should pay for it, like they did for everybody else. But I don't think they should be making vaccine passports for kids. Absolutely not.”

Walls goes further: “I personally don't think we should be vaccinating [low-risk] children if we're primarily trying to prevent infection in other people.”

McIntyre says there is precedent, with Britain introducing a flu vaccine for kids to prevent them infecting older, more vulnerable adults.

But if that's the goal of vaccination, that needs to be very clear, he says.

“Are we vaccinating them to protect them as individuals ... or are we vaccinating them because we think if we reduce infections in kids, it's going to protect other people?”

McIntyre favours a single dose for starters, with no pressure for everyone to get double-jabbed within three weeks.

IMAC's Turner says it's “reasonable” to consider vaccinating kids primarily to protect the community, as long as you're “very sure” the jab is safe for children.

“You've just got to be very honest about what you're doing. Because of the numbers game, with the Delta variant, even though the majority of kids won't get very sick, there will be the occasional child that will. So there is a small argument for individual protection, but I think the community protection argument is probably stronger.”

Immunisation Advisory Centre medical director Nikki Turner, right, says vaccinating children to protect adults might be reasonable, but you would need to be very honest about the jab’s purpose.

Immunisation Advisory Centre medical director Nikki Turner, right, says vaccinating children to protect adults might be reasonable, but you would need to be very honest about the jab’s purpose.

Would vaccinating children reduce spread anyway?

It's still unclear exactly how important kids are in the spread of Covid. Because children tend to get milder disease, sometimes with no symptoms, they should be less infectious.

A study of transmission in schools and early childcare centres in Australia found the virus tended to pass first from adult to adult, then adult to child and lastly child to child.

An Australian modelling report found even vaccinating 12-15-year-olds would have only a small impact on transmission.

But again, it's a numbers game. If other age groups are all vaccinated, and there's a mass outbreak among children, just having more infection circulating will inevitably result in more cases in adults, and more breakthrough infections in the vaccinated.

Covid modeller Michael Plank says vaccinating children would make a small difference to the R number, but that would have a significant impact over time.

Covid modeller Michael Plank says vaccinating children would make a small difference to the R number, but that would have a significant impact over time.

Michael Plank, a Canterbury University mathematics professor and Covid modeller, says the models predict that vaccinating 5-11-year-olds would reduce the R number by 0.1-0.2. That's the average number of people a Covid-infected person passes the virus on to.

That would significantly reduce the virus's spread, and therefore reduce hospitalisations and deaths in other age groups, Plank says.

“The reduction in the R number may look relatively modest, but that can have a big impact over time, because of the exponential nature of spread.”

However, it would still be difficult to justify vaccinating children if the benefits did not outweigh the risk for the individual child, Plank says.

Which brings us back to Winters, and making decisions on behalf of people who are not just little adults.

“The child has to be at the centre of your decision-making.”

Read the article HERE